There is a category of images in the Eastern Church known as “Not Made By Hands.” These are a miraculous category of images that come to us directly from Jesus or Mary rather than through the mediation of an iconographer. Some of the most famous of these images in the Roman Church are the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the Veil of Veronica, and the Shroud of Turin (though the Shroud belongs to the East just as much as the West): the images imprinted upon their cloths are miraculous and not the work of human artists. In the East, there is a particularly famous “Icon Not Made With Hands” known as the Mandylion, the Holy Napkin, or the Image of Edessa.

There is a category of images in the Eastern Church known as “Not Made By Hands.” These are a miraculous category of images that come to us directly from Jesus or Mary rather than through the mediation of an iconographer. Some of the most famous of these images in the Roman Church are the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the Veil of Veronica, and the Shroud of Turin (though the Shroud belongs to the East just as much as the West): the images imprinted upon their cloths are miraculous and not the work of human artists. In the East, there is a particularly famous “Icon Not Made With Hands” known as the Mandylion, the Holy Napkin, or the Image of Edessa.

The story of this image is not found in scripture, but it is firmly rooted in Tradition and history. A Syrian king named Abgar, who lived during the time of Christ, suffered horribly from leprosy. The fame of Jesus, which “spread throughout all of Syria” (Mt 4:24) reached Abgar at Edessa and he believed in Jesus as the Son of God. Abgar sent a messenger to him with a letter asking for Jesus to come and heal him as well as to live with him so as to escape the Jews, who sought to kill him. The messenger that he sent was his royal portrait-painter named Ananias. If Ananias could not convince Jesus to come with him back to Edessa, he was to paint a portrait of the Savior that he might be healed in that way.

When Ananias arrived, he could not get near Jesus because of the crowds and so, at a distance, he attempted to paint the portrait from a high rock. His effort proved unsuccessful and Jesus, seeing him, called him by name to come down. He gave to Ananias a letter to bring back to Abgar praising his faith and explaining that he must go up to Jerusalem to fulfill the Father’s will. He promised that he would soon send his disciple Thaddeus to him soon to heal him of his leprosy and lead him to salvation. In the meantime, Jesus took a face-cloth and washed. When he wiped his face clean, a perfect image of his face was left on the cloth, which he gave to Ananias to bring back to King Abgar.

When Ananias returned back to Edessa, King Abgar reverently pressed his face to the cloth and was almost completely healed of his leprosy. His full healing came when St. Jude came to preach the Gospel and baptize him. Abgar, in commemoration of the event, enclosed the Holy Napkin in a frame of gold decorated with pearls and precious gems and placed it over the gateway to the city. Above the icon, he engraved the words, “O Christ God, let no one who hopes on Thee be put to shame.”

When Ananias returned back to Edessa, King Abgar reverently pressed his face to the cloth and was almost completely healed of his leprosy. His full healing came when St. Jude came to preach the Gospel and baptize him. Abgar, in commemoration of the event, enclosed the Holy Napkin in a frame of gold decorated with pearls and precious gems and placed it over the gateway to the city. Above the icon, he engraved the words, “O Christ God, let no one who hopes on Thee be put to shame.”

The icon, venerated by the people of Edessa, remained there for many years until one of the great-grandsons of Abgar fell into idolatry and decided to destroy the image. The Lord appeared to the bishop in a dream and warned him about what was about to happen. The Bishop gathered his clergy and removed it in the middle of the night. He hid it in one of the walls with a lamp burning in front of it, sealing it up with a board and bricks. It remained there for many years, to the point that almost everyone forgot about it. However, during a siege by Persian forces in 545, the Theotokos appeared in a vision to the current bishop named Eulabius and told him of the icon and that it would protect the city. The bishop found the location and pulled away the board, finding the image and the lamp still burning before it. What was more, a second image had imprinted itself upon the board keeping it in the wall. When the bishop took the image to the gates, a violent wind swept down at the flames that the Persians had lit; turning it against them and making them flee.

The image was replaced above the gates with honor, but eventually found its way to Constantinople. It is not quite known when or why it disappeared, but a substantial theory is that it was taken by the Crusaders during their rule of Constantinople from 1204-1261, but the ship it was on perished.

At any rate, the existence of this image can be demonstrated in several ways. The first is a reference from Eusebius, a bishop who was Constantine’s personal historian. Eusebius claims to have seen and translated the letters from Abgar and Jesus, yet his attempts at relaying the story are sometimes poor (for instance, he never mentions the image, which was at that time hidden). Many other Syrian sources after Eusebius reference the story (including the image) in such varying ways as to be sure that they are not all relying on Eusebius’ poor attempt as the main source and reference something more well known. St. Gregory II (715-731) mentions the story of Abgar in a letter as if it were a well-known fact. St. John of Damascus and the Second Council of Nicaea take the story for granted and offer it as an argument from Tradition that icons are a legitimate part of Christian worship.

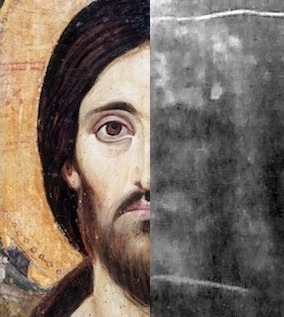

The Mandylion also helps account for why the image of Our Lord is so uniform and standard throughout iconography from the earliest times. It would make sense that they had a single source, which was easily observable (such as hanging over city gates after a famous victory). What’s more, these icons often match the Shroud of Turin (the burial shroud of Jesus) well, such as the Sinai Pantokrator, which matches the Shroud uncannily well. This would hint that the image that the Sinai Pantokrator relied on and the Shroud of Turin come from are the same face- that of Jesus.

The depiction of the Mandylion in iconography can be found from the times after it had been moved to Constantinople in 944. The icons usually show the cloth, while others show only the face of Christ. Behind his face, we see the common cruciform halo that is characteristic of almost all icons of Christ. He gazes upon us in a serene power, inviting us to come to him for healing. Yet his eyes are usually show gazing a little bit to the side and slightly upward- perhaps to indicate to us his desire to fulfill his mission on earth and go to the Father as he did to Abgar.

The Mandylion marks the moment when Christ put an end to the law prohibiting images and is a constant reminder to us that Christ has become flesh. We can rest assured in our veneration of his image because it was first given to us by Jesus Christ himself, the first iconographer, for his glory and honor as well as for our healing.

To see all of my posts on Iconography, click here.

To see more icons of the Mandylion, see the gallery below.